A Glimpse into the FUTURE of Digital Painting

One of the hallmarks of traditional painting is its physical presence. As viewers, we tend to pay the bulk of our attention to a painting’s pictorial content. On a more subconscious level, we are aware of the painting’s matière —the three-dimensional texture and impasto buildup of painted brush strokes. When a painting is photographed, this physical presence is at best implied by the manner in which the painting is lit. For example, the use of directional side-lighting emphasizes the painting’s surface via highlights and shadows.

Digital painting in virtual 3D (also referred to as two-and-a-half dimensions, or 2.5D) has been around for awhile. This visual effect is achieved by borrowing some tricks from the 3D rendering side of the tracks. The use of a height field —an extra grayscale channel in an image that uses gray values to represent a brush stroke’s height— is illuminated with a user-adjustable virtual lighting model, creating a 3D visual illusion. Brush color is simultaneously applied in concert with the height field. The result is a painted image that appears to have the three-dimensionality associated with a traditional painting.

Recently, an intersection of technologies has emerged that enables stunningly accurate 3D reproductions of traditionally painted artworks. Verus Art of Norcross, GA utilizes advanced laser imaging and Océ Arizona UV flatbed printer elevated printing technology to create high quality reproductions of famous paintings. Elevated printing utilizes a series of layered representations of a 3-dimensional scan —in this case, an oil painting— and builds up height via multiple layers of ink.

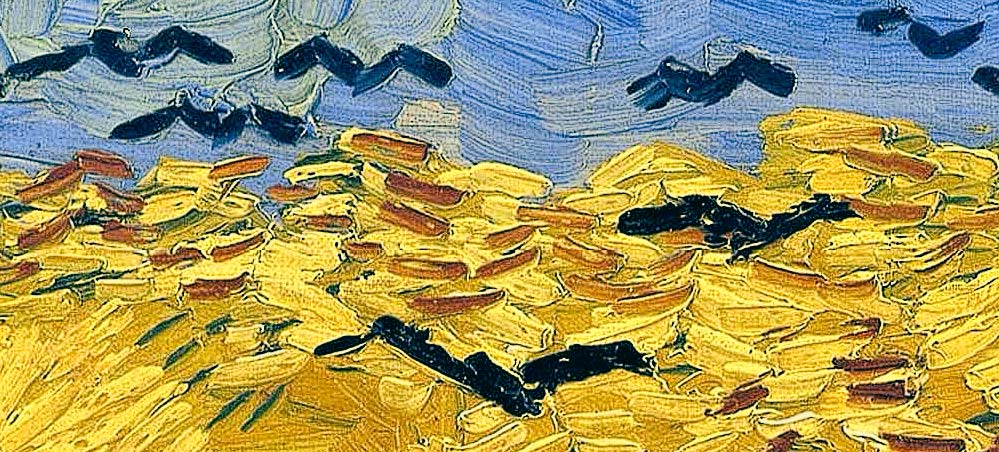

Verus’ initial project is a collaboration with the National Gallery of Canada. The collection includes several works from textural masters Van Gogh and Monet, as well as other European luminaries such as Degas, Gauguin, and Cézanne. Verus was allowed to scan several paintings the NGC collection. The resulting reproductions are done as limited editions and are priced in the $2,500-5,000 range (example below of Verus' 3D printing).

Allow me to add up what I’ve discussed thus far: the 2.5D digital paintings we today create onscreen will soon be capable of being 3D printed to reveal the thick impasto buildup depicted on the display. The key missing component currently preventing this is the ability to output a 2.5D digital painting in a format that a specialized 3D printer understands. Once a compatible file format is in place and a 3D printing service offers prints from user files, impasto style 2.5D digital paintings will be capable of being recast in the real 3D world.

I'm not suggesting that traditional oil painting is now irrelevant. But consider this: we tend to be comfortable with what we know. Change can be disruptive. Take a look at the invention of the automobile. The public initially dubbed autos a horseless carriage for the sake of familiarity. Another example is Greek temple architecture, whose original construction material was wood. As stone replaced wood building materials, the shapes of elements —columns and entablature, for example— remained the same.

In these and innumerable other cases, new materials have resulted in new forms. While it may be initially entertaining to recast an oil painting into a new medium, in the long term these mimicked forms will evolve beyond the limits of the older medium it imitates.

Advances in nanoscale science and engineering are already producing new classes of coloring materials that will eventually make their way into commercially available art materials, including paint and inkjet inks. These new colorants utilize structural coloration rather than dyes or pigments. The perceived color doesn’t arise from pigmentation, but from the light scattering off nanoscale structures embedded in its wings.

Structural color is the production of color by microscopically structured surfaces fine enough to interfere with visible light. For example, the brilliant iridescent colors of the peacock's tail feathers are created by structural coloration. Because the produced color is light, it is both brighter and more saturated than pigmented color.

These glimpses into evolving new media offer us a peek at the kinds of expressive tools our children and their children will have at their creative disposal. Were we to travel, say, 50 years into the future —I've no doubt that we may not initially recognize what expressive painted art has evolved into.